Green Infrastructure: the Underdog of Urban Resilience

Our cities are at risk

The complex nature of urban systems mean cities are disproportionately vulnerable to threats, such that internal or external shocks pose a systemic risk. Rapid urbanisation presents ever-increasing challenges for cities, namely poor air quality, environmental degradation, and declining human well-being. These internal stresses have steadily escalating effects that further decrease the ability of cities to respond and adapt to threats, hence creating a site of high vulnerability.

Climate change is the most imminent and widespread risk threatening global cities as global warming is expected to bring higher temperatures, rising sea levels, and the increase in frequency and intensity of natural disasters. The impacts of such events are expected to severely disrupt urban spaces and communities.

London is among the global cities that are quickly expanding with an increased risk factor to climate change. London's population is expected to pass 11 million by 2050 and is ranked the ninth city most at risk in the world, with flooding being the second largest risk for the city. London faces three main flood risks - tidal, fluvial, and surface water - and the majority of the city is vulnerable to one or more of these flooding categories. These are not just theoretical risks as London has historically sustained damaging water surges. Although the construction of the Thames barrier in 1982 has, for the most part, protected London, flooding is still becoming an increasing risk. For example, the barrier was closed 10 times in the 1980s, but since 2010 it has been closed on 84 occasions. Thus, London clearly requires more diverse solutions.

Green Infrastructure as the pathway to urban resilience

In the face of accelerating global environmental change, resilience has been an emerging agenda for cities like London to reduce their vulnerabilities. The definition of urban resilience is contested amongst scholars, but it has been commonly described as "the degree to which cities tolerate alteration before reorganising around a new set of structures and processes". The pathways to urban resilience are also highly contested, but green infrastructure is gaining academic and policy significance as a tool for resilience.

Green infrastructure offers urban planners a diverse and valuable approach for developing resilient and sustainable cities by reunifying the urban landscape to the biosphere. The European Commission defines Green Infrastructure as "the strategically planned network of high quality natural and semi-natural areas with other environmental features, which is designed and managed to deliver a wide range of ecosystem services". In an urban context, green infrastructure includes green roofs and walls, street trees, and green spaces, such as parks, public gardens, allotments, and recreation grounds.

Many ecologists contend that realising urban resilience must be multidimensional in nature, making green infrastructure an indispensable feature of cities due to the simultaneous benefits it provides (other than making our cities pretty).

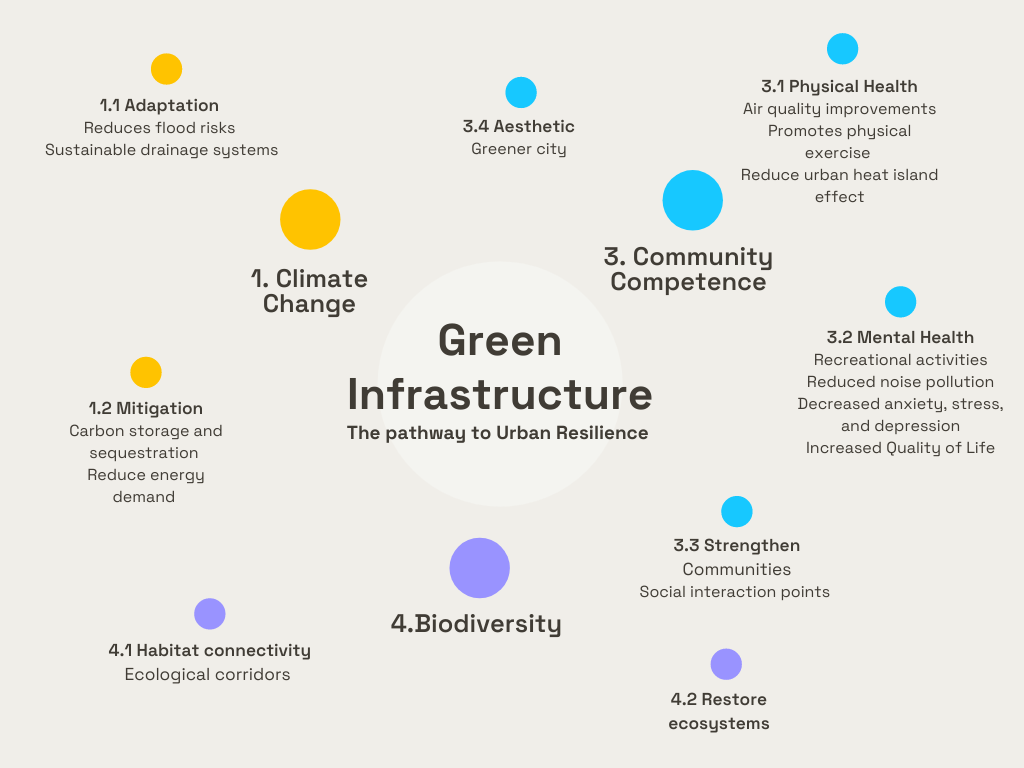

Figure 1: The multidimensional benefits of Green Infrastructure

Green infrastructure directly builds urban resilience through both climate change mitigation and adaptation. Regarding the former, green infrastructure provides cities with carbon storage and sequestration as they are effective carbon sinks needed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Additionally, cities suffer from the urban heat island effect meaning that grey infrastructure (i.e., roads, buildings, and impermeable pavements) that dominates the urban environment lead cities to be significantly warmer than their rural counterparts. Green infrastructure has cooling temperature effects when present in cities, reducing energy demand for air conditioning to further mitigate climate change. Regarding climate change adaptation, green infrastructure is particularly important for sustainable drainage systems as the permeable surfaces can absorb excess water to prevent surface level flooding compared to grey infrastructure.

Furthermore, strong levels of health, well-being, and quality of life for urban society has been argued to be an integral element of urban resilience. There is increasing evidence of the positive health outcomes green infrastructure has on society that accordingly builds urban resilience. For example, green infrastructure produces crucial physical health benefits by promoting outdoor activities and reducing air and noise pollution, as well as mental benefits such as lower stress, anxiety, and depression. Moreover, green spaces as a form of green infrastructure provide an important function in forming strong communities as a site for social interactions and overall raises society's quality of life through its aesthetic value on the urban environment.

Finally, similar to strong communities building urban resilience, strengthening our natural ecosystems provides a strong foundation for cities in the face of disaster. Urbanisation has led to the fragmentation and erasure of the natural environment; green infrastructure aims to restore the ecosystem balance that urban development has disrupted. Green infrastructure makes a valuable contribution to this by supporting biodiversity through habitat connectivity, restoring degraded or damaged ecosystems, and are particularly essential for the protection of essential pollinators, such as butterflies and bees.

However, despite the substantial body of literature that connects green spaces to the well-being and resilience of a city, green spaces are severely undermined and are not prioritised within urban planning, including London. Since the 1980s, public financing into green infrastructure has been considerably reduced, which has ultimately lowered the quality and accessibility of green infrastructure in London. In addition, green infrastructure is not a service mandated by the UK government; thus, it has been underprovided to the public, particularly in London.

How can London use green infrastructure to increase resilience?

In a highly innovative and technology-centred age, data plays a significant role in building resilient cities. The use of Geographic Information System (GIS) analysis has been an effective tool for urban planning and aiding the decision-making processes within urban management policies regarding green spaces. GIS is used to systematically model the quantity, features, and accessibility of urban green spaces. The data is then used to identify the vital ecological areas and linkages indigenous to the area and the critical sites for protection and restoration where green infrastructure can be incorporated.

For example, a study used GIS analysis across Craiova City in Romania to analyse accessibility to urban green spaces and concluded that neglected public land surrounding residential areas across the city could be used to develop green spaces. GIS analysis also includes the use of open-source data, such as Open Street Map, wherein local communities can contribute to the map. This is helpful to collect data that standard mapping fails to capture, in this case, to better understand routes taken by locals to access green spaces. GIS analysis has been widely utilised to propose urban green spaces in several major cities, such as Shanghai and a number of European cities.

GIS analysis has also been used to determine the state of green infrastructure in London. The capital scores poorly against the rest of England regarding the provision of green infrastructure across the population. Although green infrastructure consists of 48% of London, this is disproportionately located in the outer areas of London and across the greenbelt. Grey infrastructure dominates the inner areas of London, containing a lower quantity and quality of green infrastructure. Consequently, London residents have the furthest to travel, with an average of 20.1 minutes, to green spaces out of their European counterparts in Berlin, Milan, Madrid, and Paris. Moreover, due to the lack of long-term strategic planning, the existing green infrastructure is highly fragmented, so it fails to form a comprehensive green network that can provide greater benefits.

Outcomes of GIS analysis have also produced recommendations for London to improve their current state of green infrastructure. For example, as land is limited within the city, unoccupied land can be functional by utilising smaller patches of land for green infrastructure and integrating green infrastructure into new and current developments. An easy method of this would be incorporating green walls and roofs that are currently scarce in London.

In 2018 the Greater London Authority created the 'Green Infrastructure Focus Map' (Figure 2) using more advanced GIS analysis to outline existing green infrastructure across London. The aim was to help relevant governmental bodies in their decision-making by identifying where green spaces improvements and funding should be directed and what types of green spaces will be most beneficial for the needs of a particular borough, although tangible outcomes have not yet manifested across the city. Moving forward, London government authorities should utilise survey questionnaires to complement their preliminary findings to understand citizens opinions about possible urban green spaces, such as the location and features, as conducted in prior studies.

Figure 2: Green Infrastructure Focus Map using GIS by the Greater London Authority

Next Steps

There is sufficient evidence of the extensive benefits green infrastructure can provide in response to London's impending climate change risks. This warrants the expansion of small pilot projects and limited local planning into large-scale and strategic planning for green infrastructure across London. GIS creates a starting point for local London governments to develop plans for incorporating green infrastructure across the city and can be accomplished through a close partnership between urban planners, academics, local governments, and citizens to create a resilient London.